Dropping the Ball by Margie Sanderson

Recently, a friend of mine was recounting difficulties in one of her personal relationships with me. She said over and over, “It’s like every time something is not as easy as he expects, he just stops trying.” This struggle really resonated with me because I see it all the time amongst my peers and in myself. Whether it’s planning a trip to the beach or trying to get a credit card, when we hit speed bumps, it can cause a complete loss of motivation. We drop the ball.

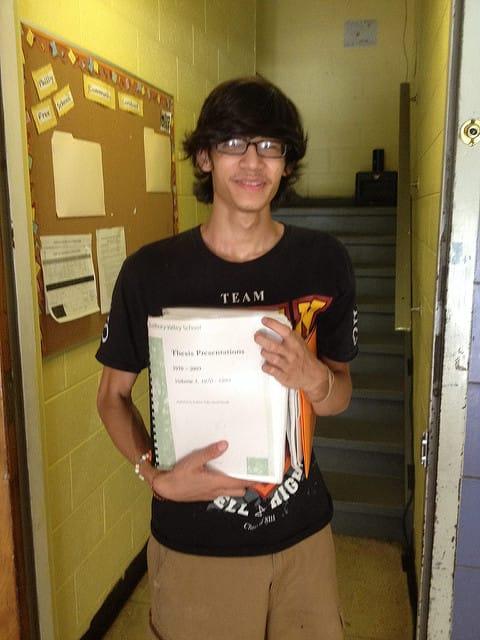

Sometimes, however, you just can’t afford to drop the ball. I consider knowing when the ball cannot be dropped a big part of the art of adulthood. It’s an important skill to develop, and there’s a lot of nuance to it. If you have a passing thought to plan a trip to the beach but don’t move forward with it, that’s no big deal. If you plan a trip to the beach and your friend pays for the hotel but you don’t move forward on planning transportation, it is a big deal. If you drop the ball on paying your bills, there are unfortunate consequences. Luckily, the democratic high school I attended gave me lots of time in my teens to grapple with responsibility and develop the skills needed to know when I can’t afford to drop the ball. I still don’t get it right every time (shout out to my landlord for accepting some late rent payments).

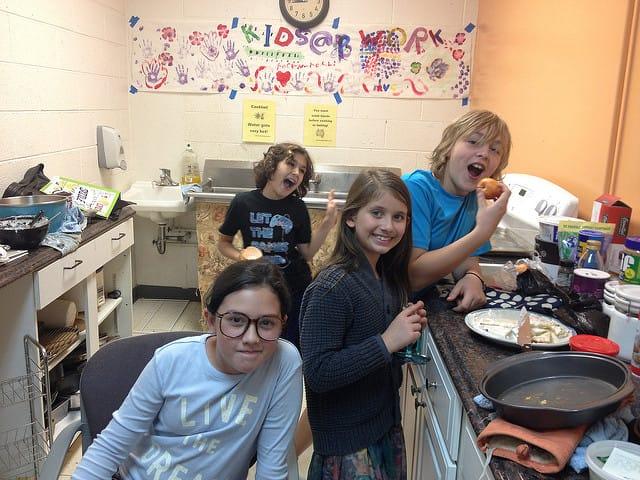

At PFS, students have an opportunity to work on these important life skills from an early age, and they struggle with them often. They make plans and forget about them, and sometimes they miss out on opportunities because of it. It can be difficult, as a staff member, to refrain from reminding kids not to drop the ball. Saying something like “Don’t forget to go meet Michelle in the art room so you can get certified for painting!” feels like a gentle reminder that helps kids do what they want to do. And some of the time, it is completely appropriate. Sometimes though, the most supportive thing I can do for a young person is to sit back and let them fail. Let them forget. Let them miss out on opportunities because of it. Giving kids the opportunity to forget, and to see the consequences of their own forgetfulness, is essential not only to this model of education, but to kids’ development into successful adults.

Giving kids the opportunity to forget, and to see the consequences of their own forgetfulness, is essential not only to this model of education, but to kids’ development into successful adults.

In the competition-driven environments created at many schools, kids have fewer and fewer low-risk opportunities to fail. Every task seems too important and the consequences too lasting for adults to let kids work them out on their own. What these well-meaning grown ups miss when they refuse to give kids this independence, though, is that learning failure when you are young and the consequences are small is hugely important. It provides a priceless opportunity to develop your ability to motivate yourself and get things done as you grow up. If a child misses out on a cool project because they forgot to get certified for painting, they’re presented with an opportunity to learn time management while the consequences are considerably smaller than they may be later in life.

Not only does a PFS education teach you how to fail, it also teaches young people that all people, some of the time, do drop the ball. As a child, I truly believed that becoming an adult was about reaching an age where you never screwed up anymore. PFS students get to see that in reality, it’s about developing the skills to know what to let go and what to pour energy into. Because our environment is age-mixed, kids have real relationships with other people of a wide variety of ages and get to see that all these people, young and old, experience successes and failures in their lives.

In many environments, adults who want the best for kids make sure that they don’t miss out on valuable opportunities. On the contrary, PFS creates an environment that doesn’t aim to provide opportunities, but rather that opens education up for kids to fully create the opportunities they seek for themselves. Obviously, supporting kids is important. We do a lot of this at PFS too. Sometimes this is setting a timer for a kid who can’t yet tell time, or reviewing a teen’s resume to help them polish it before they apply for a job. Sometimes it is helping someone write up a complaint or tie a shoelace, while other times, it is letting them struggle through these tasks on their own.

Much of the support we provide as staff is by modeling the art of adulthood, through making thoughtful decisions all day long on how to set priorities and get things done. When we stop what we are doing at 3:00 and begin cleaning up, it is a way of signalling that tidying the school each day is not a ball that can be dropped. When we choose to skip a music co-op meeting, we are demonstrating that something more pressing than the selection of new drum heads is on our plates, and that we trust the other members of the co-op to handle it. If no one shows up to the meeting, and no drumheads get purchased, the ball gets dropped. The next time we are unable to play the drums, we will have to live with the consequences of our decision, and figure out how to redirect our energies going forward. The students are watching these tiny decisions, day in and day out, and using them as data points in creating their own internal compasses for when to drop the ball and when to make sure it stays in the air. They are also watching how we react when we drop a ball-- our disappointment, frustration, and regrouping. Being a staff member at PFS means learning the incredibly complex definition of “helping kids,” which sometimes consisting of direct action, sometimes of deliberate inaction, and sometimes of modeling behavior. It means creating a space where we can all drop the ball, pick it up, and keep on playing.