PFS Is Hope

by Marie Winters, PFS Parent

My daughter attends the Philly Free School. It’s a school that is based on the Sudbury democratic model of education. All learning is student directed. Students choose how best to spend their time, deciding what to learn and when instead of having a prescribed curriculum. At the same time, students are given a tremendous amount of responsibility and are tasked with not only finding a way to make that learning happen, but also the day-to-day running of the school. One of the ideas behind this model as I understand it is that children will learn how to be productive members of a democratic society if they function autonomously in a democratic environment throughout their education. My daughter enrolled in PFS in its inaugural year when she was just four years old. She’s ten years old now. She’s had five and a half years of democracy and autonomy under her belt, five and a half years of having an equal say in her education and her daily environment.

Madeline has never had a formal history, social studies or civics class, but you wouldn’t know it. This past presidential election piqued her interest more than any other election has. She discussed politics with just about all of the students and staff at PFS. She had the time to carefully consider the merits of candidates from Sanders, Stein and Clinton, to Johnson and Trump. She compared and contrasted Tim Kaine with Mike Pence. She dove into our Pennsylvania state senatorial campaign and learned about the platforms of Pat Toomey and Katie McGinty, and compared it to the candidates in the presidential election. Through this all she formed some very firm convictions about the candidates and their platforms; convictions largely shaped from the diversity of backgrounds and world views at her school, her ability to get to know these different students freely as individuals, and existing in an environment where each of these children has the same rights as one another and as the adult staff members.

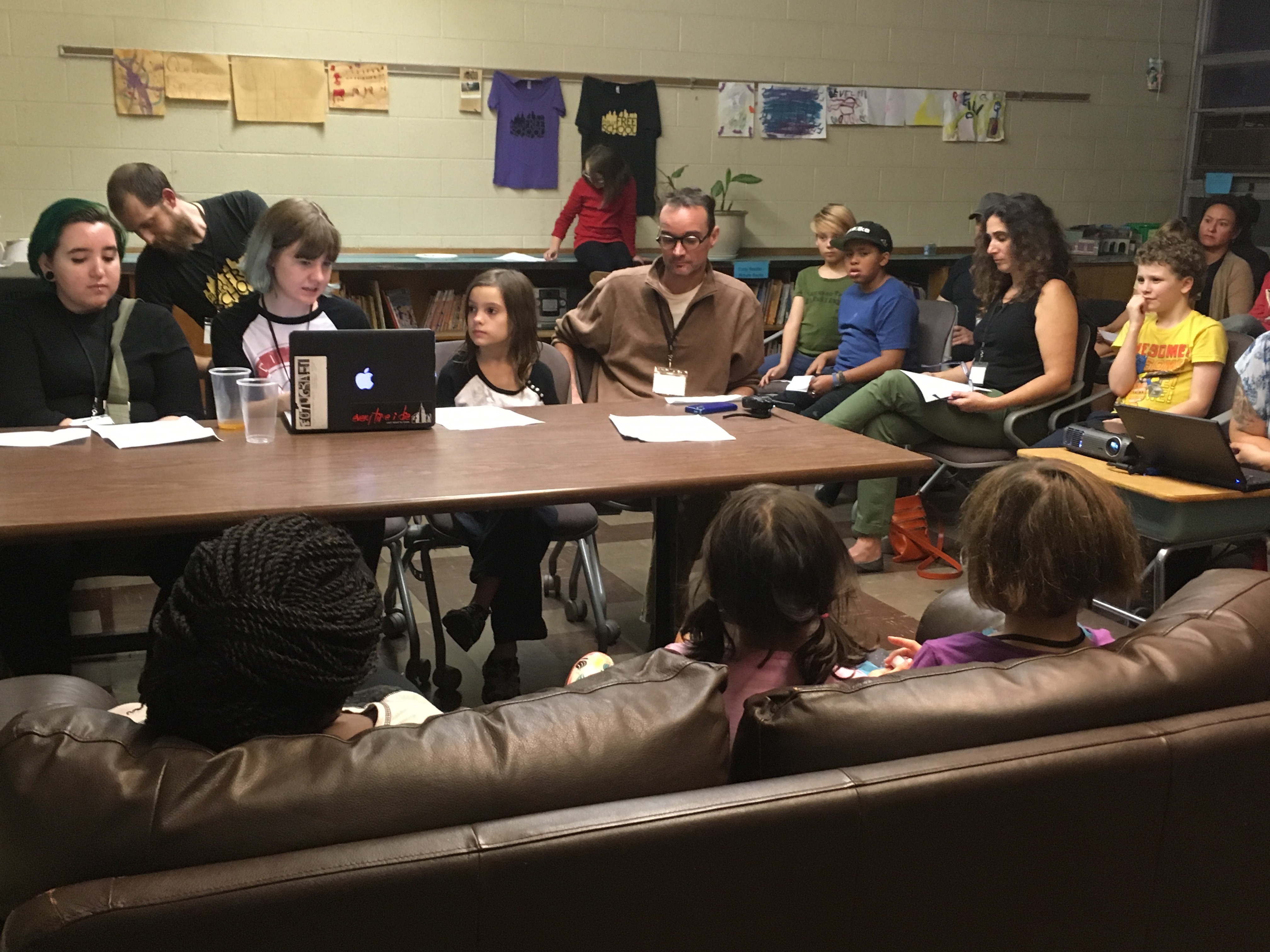

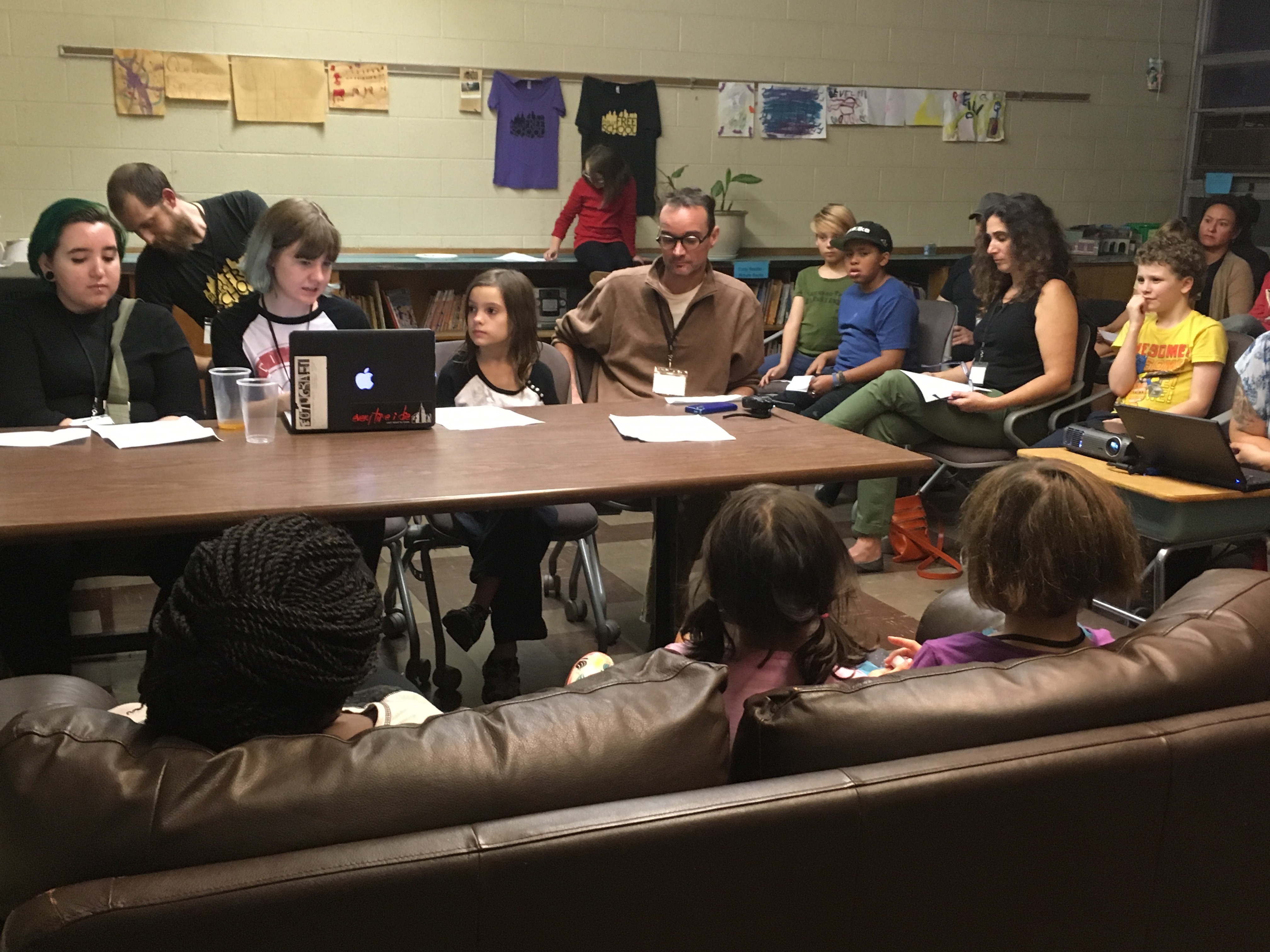

Students and staff serving on our Judicial Committee

Students and staff serving on our Judicial Committee

I think it’s remarkable that Madeline goes to a school where she has the same voice as any adult on staff, where her opinion matters just as much as anyone who is six or forty-six. Also, she doesn’t see learning as something that must happen during school hours; she sees no separation between what happens in school and what happens in the world outside of school. She lives her passion, and life is her education. So, simple knowledge about this past election was not the end-point. She spoke to people outside of school about her ideas and tried to sway their opinion. She attended political rallies. She decided to canvass for the presidential candidate of her choice based on her beliefs and her knowledge.

On election night, after the results started rolling in and it became clear that Madeline’s candidate wasn’t winning, we went to bed. I assured her that the results didn’t change who we are, and how strong we are. Maddy said that she felt bad because she thought that she hadn’t done enough to change people’s minds and influence the outcome of the election.

When I mentioned to my friend what my daughter said that night, she vehemently disagreed. “No, that’s wrong,” she said. “It was our responsibility as adults to change this outcome, not Maddy’s. We failed her and her whole generation.”

But the thing is, Maddy would disagree with that statement. The only difference she sees between us is that I’m allowed to vote and she’s not. (Just let her get started about the ageism inherent in that!) She is already taking responsibility for influencing the world around her, not just influencing her school environment. She sees herself as an agent of change – and she feels a responsibility for making the world a better place.

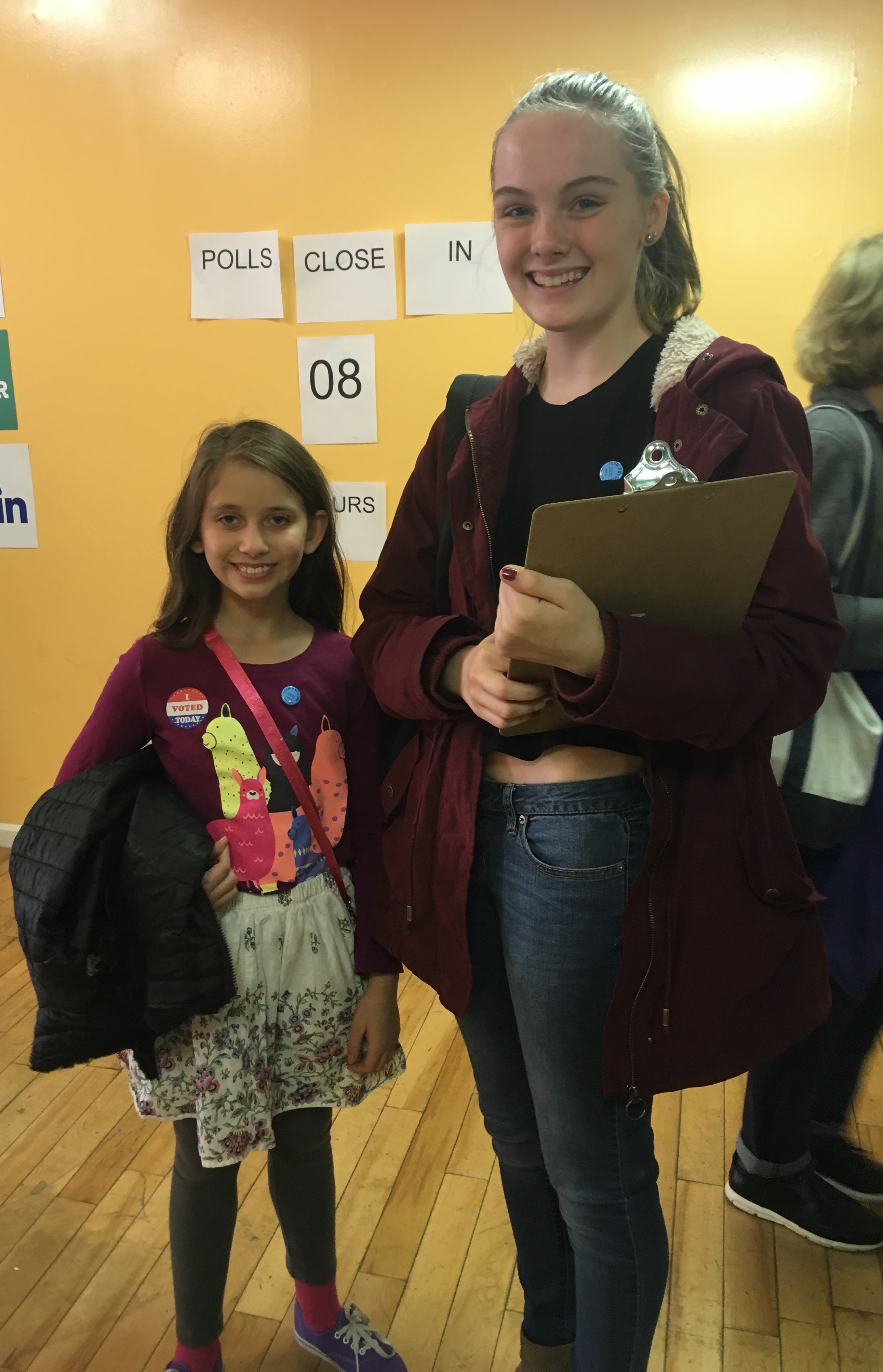

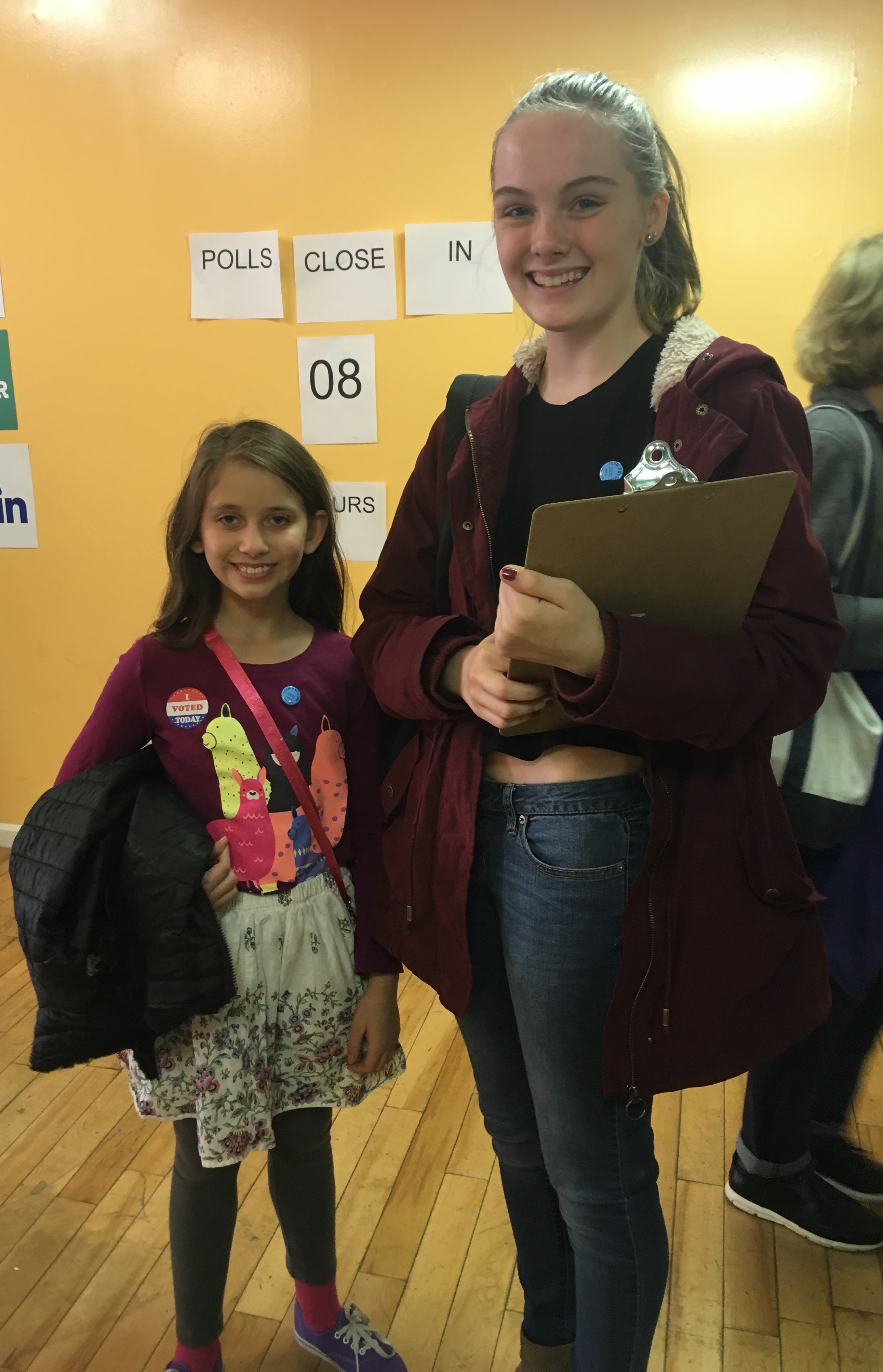

PFS students canvassing on election day

PFS students canvassing on election day

The morning after Election Day, Maddy got up and replied to an email she had received from her candidate of choice during the run-up to the election. She told her that she would continue to fight for women’s rights and for people of color because she thought it was important, and because “it might change the country”. When I saw her email I cried – I was crying a lot that day, but they were tears of hope as much as sadness.

I have no doubt that the everyday respect, responsibility, and the core democratic processes that the children at PFS are part of have indelibly shaped them. They know they are responsible for being the change they want to see – whether it’s championing a sleepover, changing a chewing gum rule, or influencing a national election. Sometimes I wonder if such a strong feeling of responsibility is too monumental for someone so young to handle, but I also believe the knowledge that you can positively impact the world around you is necessary to bring about any kind of change – in your life, in a school, in the country, in the world.

Maddy didn’t have a mock presidential election at her school, like some other schools did. She was part of the actual presidential election, and I know she will be part of the actual presidential election four years from now. She told me so before bed on election night. “Mommy, the next election we’ll start early. We’ll go from house to house and talk to people. You’ll have to take off early from work. We’ll do it together.”

This is the power that democratic education holds. For me right now, PFS is powerful. PFS is hope.

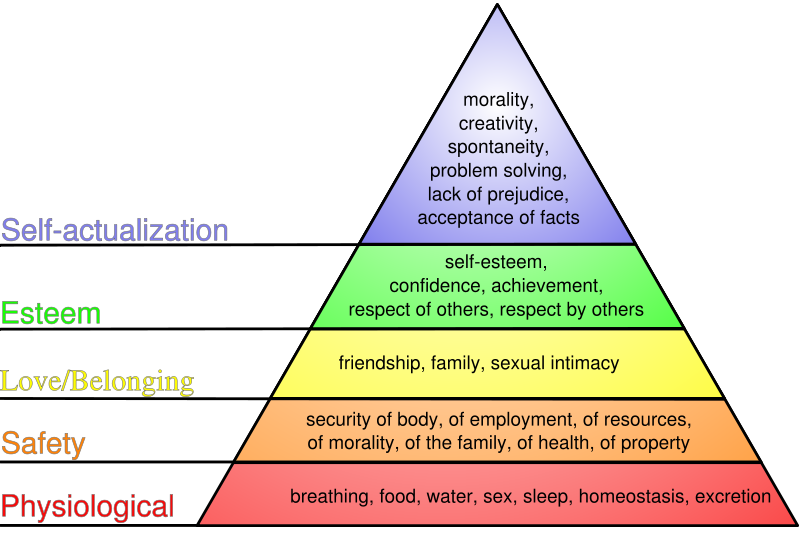

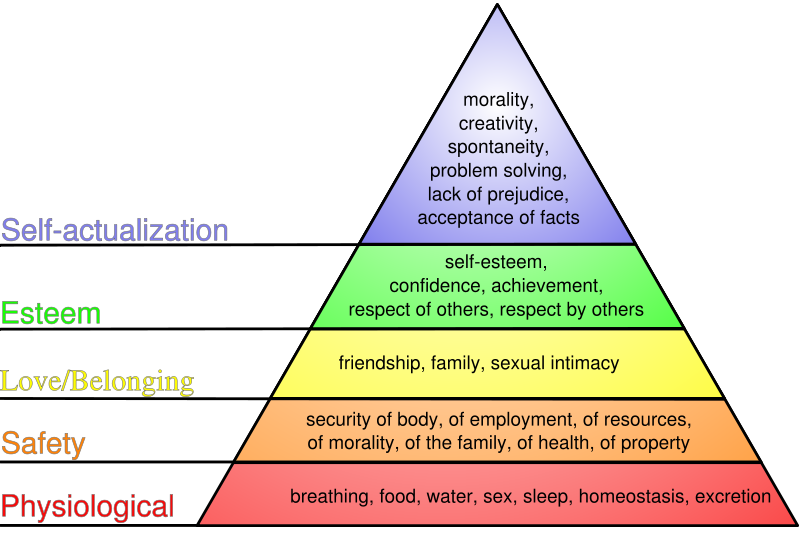

My friend recently posted a meme on his Facebook page declaring “Maslow before Bloom,” with the comment, “My teacher friends will get this!” The meme combines references to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which states that a person’s basic human needs must be met before one can begin addressing matters of the head and heart, and Bloom’s Taxonomy, which is a ranking system for educational goals. This idea isn’t new: a student’s fundamental well-being must be secure before educators can set objectives for her intellectual growth. Most teachers have witnessed the ways in which severe stress interferes with a student’s ability to learn, and this phenomenon is born out by research1.I have seen this at the Philly Free School. Some students arrive after very stressful experiences elsewhere, experiences that effectively shut the learning down.

Sometimes, it is simply clear that conventional school was not working, and the family casts about for something different. Other students are leaving situations that were truly awful. In some cases, the damage is so severe that the student’s mental health is disrupted2. The families are a bit like refugees escaping a storm, in the weather-beaten expressions they wear, the resilience they demonstrate in having found us, and the impressive courage and imagination they show in fashioning shelter for their tempest-tossed child. The student, often a teen, is typically wary, distrusting the claims we make about the freedom she will have at our school. The parents, on the other hand, are in crisis mode and need an escape hatch quickly. They are seeking reassurance that their child will be safe-- emotionally, physically, and intellectually. For parents, the essentials from these foundational levels of the pyramid need to be supplied by any new school situation. When they believe that PFS can do this, they sign up. They are eager for the hurting to stop and the healing to begin.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

And it does. Kids who wash ashore at PFS from unpleasant previous experiences are free to detox in whatever way they need. Some sleep on the sofas at school-- a lot. Some break rules to test the claims of freedom and accountability made during the admissions process. Some keep to themselves for months, diving into books or tablets or handicrafts. Eventually, the storm clouds begin to clear. Time and trust are immensely powerful healing agents. When the community continues to greet them each day and stay out of their way, while maintaining the joyful business (busy-ness) of the school all around them, it works as a stabilizer. The skittish storm survivor, stretched out on a sofa watching YouTube, watches staff people closely, expecting hints of reproach or judgement. When none arrives, she settles a little bit more into her new (old) skin.

At some point, when they feel safe enough, they begin to join in. Sometimes they start by sitting in on Judicial Committee or School Meeting, lurking in the wings, not voting or discussing, just observing. Other times they begin by tentatively reaching out to an age peer, usually another castaway who shows signs of being responsive, but not demanding. After weeks of small chit chat, they might trek to the corner pizza place together. Ah, friends! Remember those? Occasionally they will head down to the basement, which is our school’s rambunctious play zone, and before you know it, they are knee deep in a game of Hide and Go Seek in the Dark, or a wrestling match, or an improv session in the music room. It makes my heart sing to walk by the mat room and catch a glimpse of a recently enrolled teen whooping it up with a gaggle of 5, 7 and 9 year olds.

This clearing of the skies often occurs at home, too. After a few months at PFS, the parent of one teen reported: “She says I love you to me again!” The silence and moodiness that parents experience when their teen is in a school that is not working contributes to the feeling of being battered by a storm. When the teen begins healing, it is as if sunshine is peeking through. Inside the defensive teen, the open, younger child reemerges, and the parents recognize her again. The nightly battles over homework, which used to consume the bulk of the time they had to spend together, are replaced by an easy banter. The student might not share the secrets of her soul right away, but the parents can see the storm clouds lifting, and peace returns to a household where fighting and worry used to dominate. The parents feel vindicated that, indeed, their kid is alright.

This is where continuity is needed. The gifts of time and trust work slowly, incrementally, like a tiny stream eroding a centuries old rock. You can’t point to the moment it occurred, or the action that caused it, but suddenly a crevice exists where none was before. The student has begun to return to her former self-- lively, open, joyful. Because the process is so gradual, sometimes the family suffers a form of amnesia, where they forget the storm they just escaped. The parents, and sometimes the students themselves, are so relieved that they occasionally forget the elements that brought about this transition, and they begin talking about returning from whence they came. They suggest they not return to PFS the following year, or, sometimes, break their commitment to see this school year through, because there is no longer anything “wrong.”

Why does she still need this wacky school? She’s fine! How can they explain this odd educational choice to their relatives, neighbors, and colleges, now that she is once again a typical kid? The teen is faced with, and often a party to, returning to the same unhealthy environment she so recently escaped. Or the family proposes a switch to yet another educational setting. Whatever that new option is-- a different private school, a cyber charter, homeschooling-- I posit that it is unlikely to provide the time and trust, the personal freedom and community responsibility, that worked so well at PFS. While still recovering, just emerging from the storm shelter, the teen is faced with navigating a huge transition to another environment, with new demands, different staff, and unknown students. This undercuts the healing process, and throws the teen headlong into another gale force wind before she has even found her footing.

This juncture is perhaps the hardest one for the family, maybe even harder than deciding to enroll the student in the first place. The family’s trust, in both the young person and in the school, is put to a new test. What the student needs more than anything at this point is continuity. The storm that she survived in the other environment was like a tornado that devastated the land. She is working hard to reestablish the healthy layer of rich, protective topsoil so she can plant new crops. Leaving after only a year or so deprives her of the chance to reap the harvest of her efforts. Given continuity, the farmer gets to enjoy some of the fruits of her labor, even while the planting continues into new seasons.

A young person who has been through a difficult school experience is just becoming reacquainted with herself, and needs time to discover what she wants to do with her life, and how she will get it. Grappling with what she might choose might be the most terrifying thing for the student and her parents. Allowing her to remain, in a healthier state, means allowing her imagination to call the shots on what she will do with her time and talents... destination unknown. This is an act of true courage.

Many young people who come to PFS are only just emerging from the “Maslow stuff.” They need more time, and more trust, so that they can take on the “Bloom’s stuff.” Continuity works a powerful magic that the student needs in her bag of tricks. As Tolstoy put it in War and Peace, “The strongest of all warriors are these two — Time and Patience.” I always hope that families will hold on, hang in there, and allow the young person to stay at PFS, which is uniquely suited to support them in this kind of important work.

1 “Many studies have confirmed that both working memory and long-term memory are inhibited by stress. Working memory is a term for the "capacity of attention that holds in mind the facts essential for completing a given task or problem. Stress sabotages the ability of the prefrontal lobe to maintain working memory."” (Goleman, Daniel.Emotional Intelligence, Bantam Books, p. 27, 1997.)

2 Evidence that the mental health of young people has declined dramatically recently, and school as a significant factor in this decline, can be found here.

Students and staff serving on our Judicial Committee

Students and staff serving on our Judicial Committee

PFS students canvassing on election day

PFS students canvassing on election day