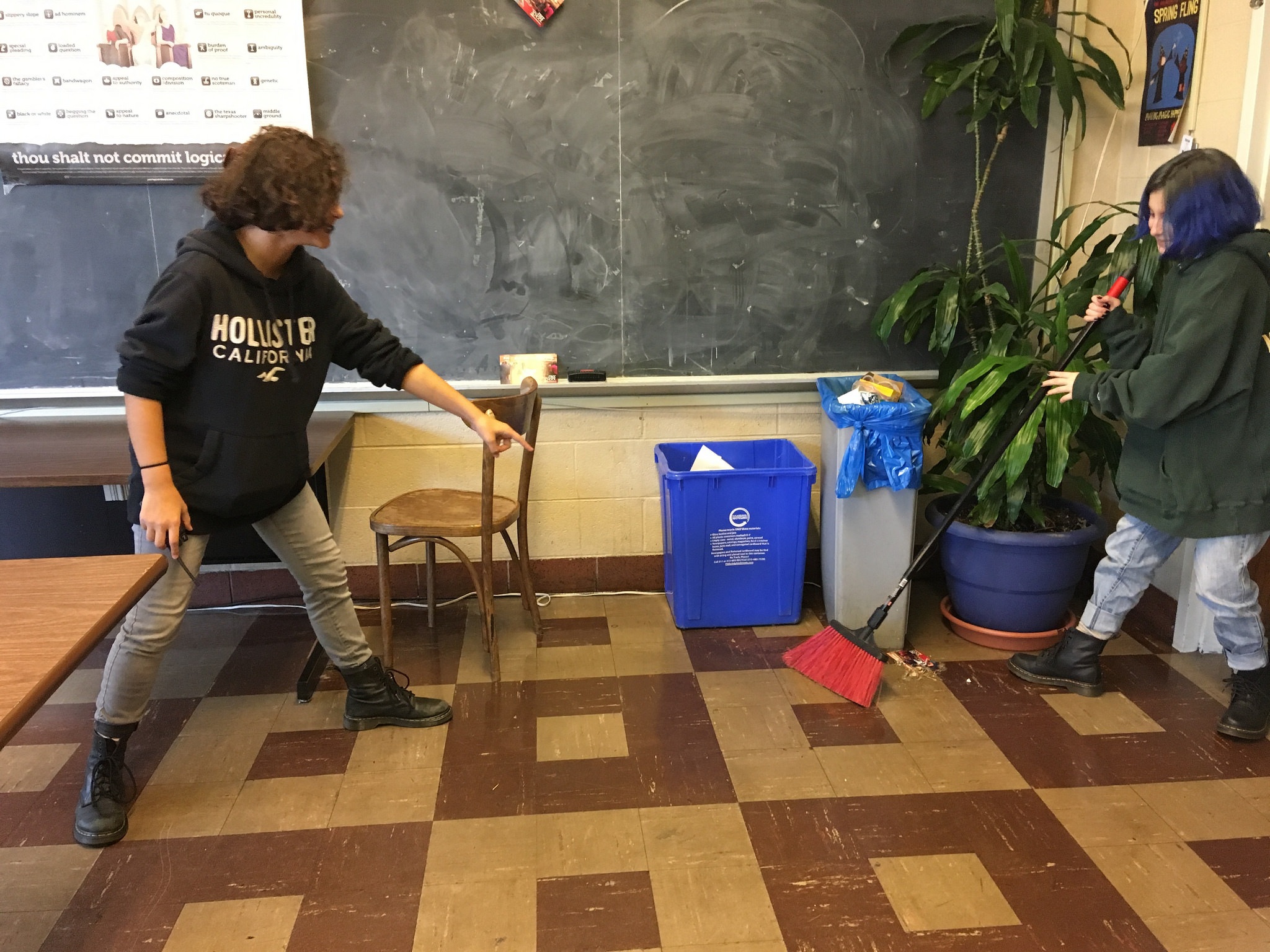

One of the responsibilities of every School Meeting member at the Philly Free School is participating in Clean Up. For about 15 minutes at the end of every day, our whole community comes together to put the school back in good order after a day of wildness, fun and learning.

Getting 85+ people engaged in cleaning a huge school building at one time is no small feat. To meet this challenge, School Meeting has created a system where everyone is assigned a space to clean, under the leadership of a Clean Up Clerk. The Clerk is assisted by two deputies, called Zone Leaders, who provide oversight in certain regions of the building to ensure that the tasks are getting completed. No one can go to the Roller Rink to play with their friends and prepare for departure until the Zone Leaders and Clean Up Clerk are satisfied with the quality of the work done in each room. These year-long positions are filled via elections at School Meeting, and they make a big difference to the culture of the school.

As Media Clerk, I interviewed Noah Mogliewski (17), Clean Up Clerk, and Nadja Mogliewski (15), Zone Leader, to share their stories about taking on these important roles. Here are excerpts from that conversation:

Michelle: Why did you run for this position in the first place?

Nadja: I started cleaning and Reb (a staff member) said “You’re good at that!” so I became a Floater [cleaning wherever there was a gap]. Then he said, “You’re good at THAT too!” so he asked if I would run for Zone Leader.

Noah: The school needed someone to run for the job and Reb suggested, “Brother-sister combo?” I thought, “Sure, why not?”

Michelle: What is rewarding about the job? Why do you continue doing it?

Noah: It’s nice not being stuck in one area. I can be everywhere. I love resource management—I look for games with a lot of it resource management involved. This is like that.

Nadja: I like helping out. When I first started, I didn’t know a lot of the kids’ names. Now I know them all, and my friends who started at PFS before me don’t. It’s rewarding to be part of such an important job at this school. It’s something that I’m good at—organization. Sure I can clean, but this is using my talents better.

Michelle: What are some of the challenges of being Clean Up Clerk and Zone Leader?

Noah: I have to be everywhere. I have to lug the vacuum up and down. Some people aren’t in their area and it’s not worth it to fight with them about it. Where do I put this empty box? The computer lab team is hiding brooms, again!

Nadja: Well, I’m short, and young, and my voice is high—it’s hard to get people to do their jobs. It’s a matter of commanding authority, or maybe simple respect. Gender is part of it. I am friends with some of them, so that makes it hard.

Michelle: Were there any surprising elements to the job?

Noah: It was explained to me that kids run things here, but it wasn’t clear to me until I started actually running things. If I don’t tell SM that we need toilet paper, we won’t have any toilet paper!

Nadja: It’s increased my school loyalty. After only going here for 6 months, I had so much PFS spirit! I think being a Zone Leader helped. The school is a life, and you bond with that life when you take care of it. Now I feel like charging into war for the Philly Free School!

Michelle: What, if anything, have you learned from the position?

Noah: It’s helped me learn how to prioritize friendship and job. Is my casual friendship with this person worth it? Can I tell them to be quiet and go back to cleaning? If I do it in a different way, it might take longer. The approach depends on the person.

Nadja: It brought good perspective on what staff go through. Only a taste, because they are doing so much. It’s a tough job, but I have learned a lot. You want good relationships with these kids, and it’s hard not to get completely angered and explode sometimes. It’s also shaping—we get to choose who goes where. It’s a huge responsibility.

Michelle: What advice do you have for future Clean Up Clerks?

Noah: Upstairs needs the Simple Green, downstairs needs the brooms! Get to know the people you assign to staff the Janitor’s Closets. Enter each room differently, because those teams are all different.

Nadja: Honestly, you have to know your people and your jobs. Pay attention to detail. Get to know the personalities. It’s problem solving!

One of the ideas that I’ve heard many, many people talk about lately in response to national political trends is the need for children to have a social justice curriculum. I understand why this would concern responsible parents. Right now, on a national level, there is political disregard for women, minorities, the poor, the handicapped, and LGBTQIA individuals, just to name a few distinct groups. It seems that the federal government’s idea of justice is that those with the most power should get whatever they ask for – often at the cost of those minorities. If a minority or other interest group wants something, they should find a way to get in power, otherwise they are losers and are out of luck. The ideals of compromise and balance of power have been lost. The idea that government has a responsibility to take care of all of its citizens seems like something from a bygone era. Many of us put our hope in institutions like the American Civil Liberties Union or the judicial branch of government. Many of us are actively seeking social justice.

So, yes, it makes sense that we should try to instill this idea in our children. We feel it’s necessary to teach reading, writing and math, so it follows that we should just teach social justice too, in order that a socially just generation might emerge from the ashes of our failure. I think this idea has merit, but I believe it’s also fatally flawed in the same way most educational systems are fatally flawed.

Generally, a social justice curriculum includes the following:

- Self-love, self-knowledge

- Respect for others

- Social movements & social change

- Awareness raising

- Social action

In a school that teaches social justice, one or more adults are going to tell the children that this is something they must do. There will be defined amounts of time where they are tasked with different activities that are designed to bring to light the need for self-respect and respect of others. They’ll learn about different social movements through history, and it will probably all culminate in a big class project aimed at some social action or another. This certainly isn’t all bad, it’s just imperfect.

How can children really know themselves when they are told what they have to do for most of their waking hours? Can a child that consistently scores C’s, or finds it difficult to sit for 6 hours straight love themselves completely? How will they respect others, when their educational system doesn’t truly respect them as individuals? And how will they act when this isn’t a compulsory exercise?

This is what I see the difference is between learning social responsibility and social justice and living social responsibility and social justice. Right now we expect our young to be told what they should be doing for eighteen years, to learn democracy in a textbook, and then emerge as a fully functioning adult ready to take part in our democracy. Right now especially, I feel this hasn’t worked out so well. Will adding some social justice training be the panacea?

My daughter goes to a democratic school called the Philly Free School. Many parents lately ask me:

- Is there a social justice curriculum?

- Are there instances of discrimination?

- What has the school done about: the election, the Muslim ban, this Senator, that proposed law, etc.?

Let me explain a little about the school. Children have autonomy. They are allowed to pursue what they would like to learn, much like we as adults are allowed to do this. The school trusts children to make these choices. The children are also tasked with running the school in conjunction with a small group of adult staff members. They are also charged with making and enforcing the rules at the school. Some of the rules that I can think of off the top of my head include no violence, no hate speech, and you cannot infringe on someone’s right to exist peaceably.

Judicial Committee in action at PFS

Judicial Committee in action at PFS

For the children at my daughter’s school, they feel strongly about keeping their school environment healthy. People don’t always do the right thing, though, and sometimes lines are crossed. When a rule is broken, a case is brought before the judicial committee. Kids and a staff member listen to the case and decide whether a rule was broken and what the consequences will be. I’ve heard about conversations at judicial committee meetings that have brought tears to my eyes. Children as young as five grapple with what it means to thoughtlessly use words that would offend, or to unintentionally (or sometimes intentionally) infringe on someone else’s rights. Kids from all over the city, from different races, nationalities and ethnicities talk about applying social justice in their own day-to-day school environment. They are not being taught, they are actively engaged in meaningful social justice in their lives.

Through the respect they are given to take the time to find their own path, they learn about themselves and learn to love themselves. They respect others easily, because they’ve likewise been treated with respect. Inevitably, these students become very interested in the ideas of right and wrong, and how justice is and is not applied in the larger world. After the last presidential election, many of the kids at my daughter’s school held a “We the People” series of seminars, where kids from eight to eighteen came up with the idea to each teach about a different civil rights topic. Since these kids have hands-on experience working within a community to bring about change, they readily and voluntarily start to do the same in the wider world. So many of the kids at PFS have been politically active lately, I know that these young people are a force for good that will only grow as they mature.

We the People Seminar

We the People Seminar

So, your questions answered:

- Is there a social justice curriculum? No. No adult is going to stress the need for children to read about or engage in social justice exercise. Children will participate in a system of justice that will materially impact their day-to-day life. Or they will learn what happens if they choose not to take part – generally frustration.

- Are there instances of discrimination? Children will sometimes make this mistake, especially considering the national political rhetoric these days. However, children get to have very genuine conversations about right and wrong, discrimination, racism, and sexism. Children get to explore this, figure out where their boundaries lie, what is acceptable, and how to remediate an issue.

- What has the school done about XYZ? The school hasn’t done a thing except exist. The school hasn’t organized protests or marches. The children, so many children, have gone out into the world and have canvassed, marched, protested, staged political theater and volunteered. I’m sure they’ve done more than I know about.

So, instead of trying to add social justice to an authoritarian form of education, consider democratic education. Consider letting children take charge instead of adding another structured activity or compulsory piece of education. Consider letting children meaningfully engage in democracy before the age of eighteen. I think it might just be the change we need.