Learning in the Face of Diversity by Michelle Loucas, PFS Staff

Of all the magical things about the Philly Free School, one of the most important to me is the diversity of its members. I believe that I am not alone in valuing this feature of our unique school. The word diversity gets used a lot in the U.S., and on a surface level, there is general agreement that diversity is a positive thing to which all schools should strive. If we are to address the major rifts in our social fabric, we need to start understanding each other’s perspectives. Yet most schools are failing at this goal miserably.

The Problem: Segregation in PA schools

Public or private, most schools in our region have a very narrow range of diversity in terms of race, socio-economics, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and geography. Race is the measure most written about, and the situation in Philadelphia is dire indeed. According to a study published in January 2015 by the Civil Rights Project, 44.5% of metro Philadelphia schools have a majority of students who are racial minorities and 30.9% of schools are considered “intensely segregated” (90-100% minority).1In 2010-2011, 17.1% of all Philadelphia metro schools earned the dubious classification of “apartheid schools” (i.e., 99-100% minority). While most of us thought the dark days of racial segregation were behind us, these statistics tell a very different story.

From where the student is sitting, her classmates look a lot like her. Although 52.8% of students in metropolitan Philadelphia were white in 2010-2011, these students are not evenly interspersed in classrooms.1 According to the study, “The typical black student in the metro area attended a school with only 17.6% white students, and the typical Latino attended a school with 29.8% white students.”1 Meanwhile, “the typical white student attended a school that was 76.8% white.”1 (The way kids of different races are treated while in school, and the opportunities afforded them there, is appalling as well, but that is a topic for another piece.) The continued racial segregation in schools has long term consequences. It means that kids are not getting to know kids with other life experiences at the age when such contact would have the most powerful effect for their development into adulthood, and for the eventual harmony of our society.

Elusive Solutions

Most schools know this is a problem but are at a loss for how to solve it. Historically-white private schools often have Diversity Committees to try to increase the number of students of color in their ranks. I personally know several brilliant, socially-conscious people on such committees at schools in Philadelphia. But trying to infuse diversity after a school’s culture is established is an uphill battle. Families of color naturally do not want to be the token representatives of their race in a school community. I know families of color who have considered enrollment at these schools but chosen not to because of the shortage of students who look like, or share the life experiences of, their kids. The numbers are against these schools as well, because the legacy of racist practices and policies in this country has left a disproportionate number of people of color unable to afford private school tuition, and unless those schools are deeply invested in steep tuition discounts for a sizable portion (not a small percentage) of students, the schools’ success in this area will continue to be minimal.

Commitment to Creating a Diverse School Community

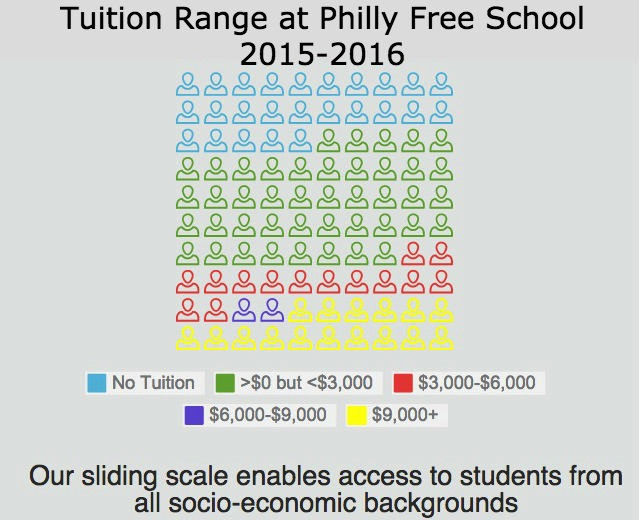

In contrast, The Philly Free School was founded, and continues to be operated, with just this deep commitment to diversity. We are proud to report that our school’s racial demographics have hovered around 50% white, 50% students of color since we opened in 2011. Of course, for a community to be truly diverse, race is only one factor. Geographically, our students hail from all corners of the city and surrounding suburbs, including parts of New Jersey and the Main Line. The students at our tiny school live in households where an impressive range of native languages are spoken, including Vietnamese, Italian, Moore, Russian, French, Cantonese, Spanish, Laotian, Arabic, Hebrew, and Swedish. PFS embraces the wide range of gender and sexual orientation identities of our students and their families. As a tuition-based school, the PFS founders were especially concerned about creating a community that was socio-economically diverse. In 2015-2016, over 20% of the PFS student body paid no tuition at all, and our sliding tuition scale ranged from $1,800 per year ($10/day for 180 school days) to $12,000 per year. Our average tuition hovers around $3,500/year. Even the upper end of our tuition scale is less than half of the tuition at many of our neighboring private schools.

Learning in a diverse environment is better for all kids.

Maintaining this socioeconomic diversity requires thoughtful, ongoing planning and fundraising by members of our community, but it is worth it. Learning in a diverse environment is better for all kids. We believe this in our bones, but there are so few studies that take this up, perhaps because there are so few racially diverse environments in which to look, that data is hard to come by. In addition, the outcomes we seek are not easily quantified-- tolerance, acceptance, open-mindedness, empathy, understanding. For these reasons, this recent study the Civil Rights Project is remarkable. And the data it provides proves our thesis. As the authors explain, racially integrated school settings:

foster critical thinking skills that are increasingly important in our multiracial society—skills that help students understand a variety of different perspectives. Relatedly, integrated schools are linked to reduction in students’ willingness to accept stereotypes. Students attending integrated schools also report a heightened ability to communicate and make friends across racial lines.

These are the elements of an education that goes far beyond the memorization of facts, the achievement of “grade level learning,” or the enhancing of a transcript. They are components of a life well-lived, within a community, defined by each individual student in her own way. This, in a nutshell, is the primary “curriculum” found at PFS.

Diverse schooling leads to positive outcomes for children of color, not just in terms of academic achievement in the short term, but also in earnings and better health later in life.1 But desegregated learning environments also help white students: “There is ... a mounting body of evidence indicating that desegregated schools are linked to profound benefits for all children.”1 And these positive outcomes persist for years to come, including a greater likelihood that children of all races who are educated in diverse settings will seek out integrated colleges, workplaces, and neighborhoods as adults, which may even lead to integrated educational opportunities for their own children1 This is why it matters so deeply that we get this right, now.

Critical Components

However, simply sitting in physical proximity to people from other backgrounds is not enough. I propose that at least 3 core components that must be in place for the positive effects listed by the Civil Rights Project to occur. These align pretty well with research done by Gordon Alport and others on Intergroup Contact Theory.2

1. Start young. Our biases, preferences, and understanding of the world sink in while we are young children. Attending a diverse college or university, or moving to a diverse community as an adult, is less likely to have a lasting and powerful effect on my ability to relate to others than my childhood relationships are. At PFS, students as young as 4 years old enter and spend their formative years alongside their diverse peers, from early childhood right through the critical teen years and into early adulthood. The diverse school community makes up the fabric of their young lives. The authors of the Civil Rights Project study summarize the effect this way: “Evidence indicates that school desegregation can have perpetuating effects across generations.”

Kids will not learn about equity in a setting where an arbitrary authority decides who participates in which activity with whom.

2. Sustain the connections. A short-term foray into the world of another group will not have a long-term effect on my understanding of how the world works. Even long-standing programs created to bridge the gap between historically distant groups, like the camp for Middle East teens called Seeds of Peace, acknowledge that the sustained contact between participants is essential for the effectiveness of the effort.3 Students at PFS have the opportunity to develop long-term relationships with peers from very different experiences. Their contact with these others is not limited to one period a day, or one year of schooling. They are not forbidden to talk to one another during “instructional time,” or moved from one cohort to another based on the master schedule demanded by a large institution. And unlike homeschooled kids, they also have a good number of fellow students at their disposal, all day, every day, for the length of their K-12 education. The peers that they interact with are not dependent on a parent’s willingness or ability to get them together. We often talk about the “gift of time” that Sudbury schools afford young people. The opportunity to develop and nurture these relationships with kids from different backgrounds is one of the most powerful benefits of this gift.

3. Share the power in a community of equals. Kids will not learn about equity in a setting where an arbitrary authority decides who participates in which activity with whom. Even at elementary schools with an impressive racial mix, the lasting effects of diversity are limited by the nature of the contact they have with one another. To address this, some schools are going to great lengths to get kids as young as 8 to talk openly about race. But these are in teacher-controlled environments, and the mandatory nature of these programs is, understandably, receiving a great deal of pushback from families.4 At PFS, every School Meeting member (students + staff) has equal power in running the school and governing their own learning. Students are learning in a true working democracy, where each individual has the same rights, regardless of age, race, gender, or academic achievement. In this community of equals, kids see those from other life experiences on par with them as a default position. Differences arise based on ability and effort, not external markers. Henry might be a better lego builder, and Jules a wizard on the guitar, while Kyra can build coalitions like a veteran statesman. But these are earned distinctions, and do not correlate with race or wealth. At School Meeting, each of these students (and the staff they elect) gets one vote, a vote no more or less powerful than any other. This makes all the difference.

Relationships at PFS

Every day I see examples of relationships forming and deepening across lines of race, socio-economics, gender, age, and geography. Because kids are free to associate with whomever they choose at our school, it is telling when they spend time with kids from other walks of life, kids who they would not likely even meet if they attended other schools. Take Thomas and Heather.5 Thomas is an African American teen who lives in a corner of the city that is overwhelmingly Black. Heather, a 7-year-old who is part Asian and part White, lives in the opposite corner of the city. For three years, this unlikely pair have had a easy friendship, playing Rock, Paper, Scissors and skateboarding together. Their rapport is simple, genuine, and deep.

Then consider Ronald, Jeff, and Scott, three preteen boys. One came from an overwhelmingly White private school, one from an overwhelmingly Black charter school, and the third from a public school with more diversity than most, where the curriculum made him utterly miserable. At PFS, these three boys spend countless hours gaming together, sharing both physical and virtual worlds. At one point they created a small business, splitting profits and responsibilities. I believe the odds are low that these students would even meet outside of PFS, much less have the time and opportunity to develop lasting relationships. As a staff person who had a severely homogeneous school experience herself,6 I find it fascinating and hopeful to watch these friendships blossom.

Philly Free School students are living what our nation purports to do: allow people from a wide variety of backgrounds to share the freedom of independent co-existence along with the responsibility of democratic self governance. On a day to day basis at PFS, we experience the truth of the Civil Rights Project findings in the interactions of the members of our community. In the long term, these are the building blocks for healing the schisms that divide our nation. I hope that more young people get this opportunity, for their sake, and for the sake of our democracy.

1 http://civilrightsproject.ucla...

2 Alport, G. The Nature of Prejudice. (1954; 1979). Reading, MA : Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Alport’s basic premises include: Equal status. Common goals. Intergroup cooperation. Support of authorities, law or customs.Personal interaction.

3 http://www.seedsofpeace.org/?p...

4 http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2...

5 All student names have been changed.

6 One source lists the current racial breakdown at the high school I attended as 91% white, 3% black, 2% hispanic, 2% Asian. I am certain that it was even less diverse than this in the 1980s when I attended.