Exploration of Self and School by Michelle Loucas, PFS Staff

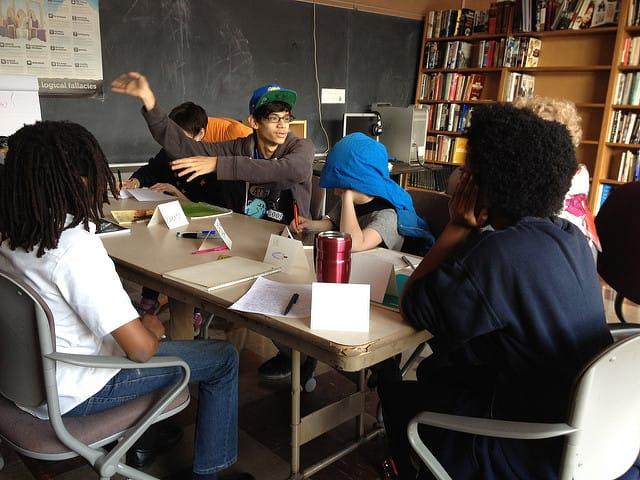

In the 2014-2015 school year, two seminars were conducted at PFS. Both were facilitated by Dr. Karen Clark, a long–time ally and trustee of the school, and a lifelong social justice advocate and educator.

I knew Karen from her work teaching courses on education, society, power, and privilege at UPenn, and when she expressed willingness to co-create a seminar with our students, I presented the idea to School Meeting members. Sufficient interest existed to invite Karen to come to campus to talk to those who were curious and begin to flesh out what the group might like to focus on. Students and staff who signed up for the seminar did so entirely of their own volition, although they were asked to commit to attending all 4 sessions in the series, for continuity. Like all activities at PFS, no arm-twisting, judgments, or secret agenda was at work in determining who participated. Those who came did so because Karen sounded interesting and the topics she mentioned appealed to them. I attribute much of the genuine learning that happened subsequently in the Seminars to the non-coercive nature of their formation.

Who are you: The birth of Identity Seminar

Although we thought the fall seminar would focus on race, power, and privilege, it evolved into a look at identity. The group was made up of half a dozen teens, two staff members, and Karen. She began by asking us to share moments in our lives that we found important in terms of our identity formation, and right from the start I was amazed at the openness and trust exhibited by everyone in the room. One person shared an experience about a time when he was wrongfully mischaracterized by a camp counselor, and the way he made sense of the incident thanks to the grounding words of a supportive parent. Another talked about the cruelty of students and staff at a previous school when he let his sexual orientation be known, and his relief at being accepted for who he is at PFS. Karen shared some of her own struggles associated with aging and society’s disregard for those past middle age. I was impressed at how seamlessly the group fell into this exchange of intimate moments. Having taught in big public high schools in the past, I had worked hard to build a community in my classroom where such personal stories could be shared, but never achieved a moment like this, where it felt that every person in the room opened themselves up and embraced the openness of others.

Ever true to democratic principles, Karen insisted on participants collectively deciding on where the seminar should go next, so that we created both the content and the methods together as we went. The sessions moved into artistic expressions of our identities, and from there to a trip to see the newly released film Birdman, suggested by a teen who had seen it and found many connections between its themes and our discussions. At our final meeting, we analyzed the film as it pertained to our study together, and then debated what the seminar topic should be for the spring semester.

Why are we here: School Purposes Seminar takes shape

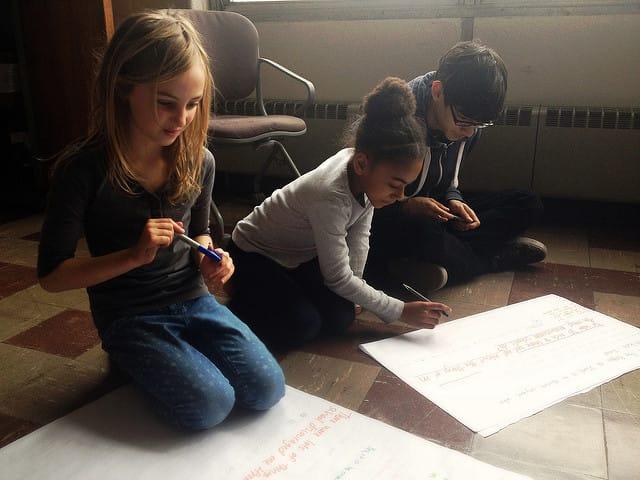

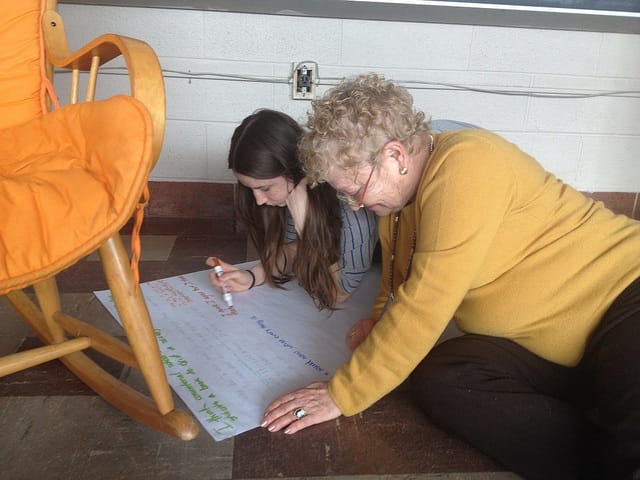

When the spring semester began, we circulated a survey to decide on the seminar topic, starting from discussion in the previous semester, asking former participants as well as anyone else who was interested. It was a contest between “How do I create social change?” and “What is the purpose of school?,” with the latter winning by a nose. In the new semester, participants varied in age from 7-70 and doubled in number. Karen again insisted on co-creating the course, but this time participants succeeded in convincing her to provide a lecture on the history of schooling in the U.S., a topic that she frequently taught graduate students. She was baffled. The conventional paradigm was thoroughly upended: given the choice of what to learn, how to learn, and even whether to learn, these young people insisted on having an old fashioned hour-plus lecture by an adult. This was because they had the power to choose each of these things, every step of the way. While Karen lectured, one student took meticulous notes on chart paper for the benefit of all. Karen only agreed to do the lecture after a session where she drew out something of the histories and experiences of her listeners on this topic. Again, students shared struggles that they had had, questions that arose for them, and personal beliefs about education.

No easy answers were reached, but the exchange was rich, and its very existence demonstrated to me, again, the power of non-coercive education.

One tool that Karen used to enable discussion from many participants at once was a “Silent Conversation.” In this exercise, we each responded to a common prompt on our own sheet of chart paper, and then circulated the room responding to, and asking further questions about, the comments on other papers. Take a look:

Silent conversation #1: Answer the question “What are schools for?”

Sample of responses:

- “to educate anyone who wishes to learn”

- “to help kids with math”

- “to prepare Americans to be educated citizens”

- “to maintain the status quo that keeps people minimally educated and young people disempowered"

- “to give students a basis to exist in society”

- “to prepare children to work in factories”

As you can see, there was an impressive range of comments. Opinions varied and everyone felt strongly about the topic, but even given the anonymity of the format, comments remained respectful and productive.

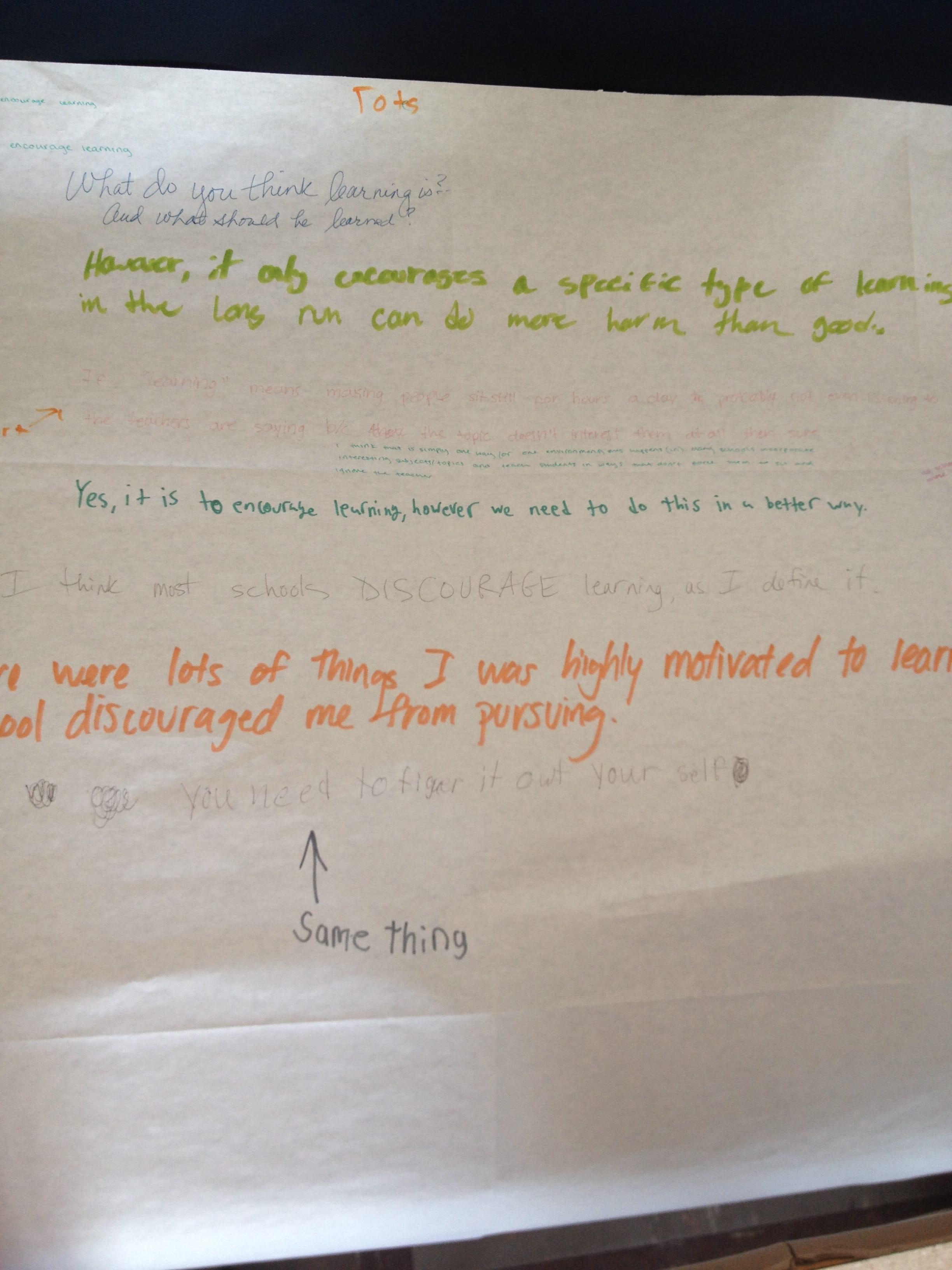

To clarify this point, you need to see what else filled those pages. Here is how the silent conversation went for one response. Each bullet point is a comment by a different participant. Indentions are comments made to other comments.

“What are schools for?”

“to encourage learning”

- Tots (totally)

- What do you think learning is? And what should be learned?

- However, it only encourages a specific type of learning, which in the long run can do more harm than good

- If “learning” means making people sit still for hours a day & probably not even listening to what the teachers are saying b/c the topic doesn’t interest them at all, then sure.

- Smart

- I think that is simply one way (or one environment) that this happens (in). Many schools incorporate interesting subjects/topics and teach students in ways that don’t force them to sit and ignore the teacher

- But with 30 kids in a classroom and 1 teacher and 1 curriculum, it is not designed to meet the needs of individuals.

- All schools do not use these ratios.

- You need to figure it out for yourself

- Same thing

- There were lots of things I was highly motivated to learn that my school discouraged me from pursuing.

- I think most schools DISCOURAGE learning, as I define it.

- Yes, it is to encourage learning, however we need to do this in a better way.

The depth of thought, and the sensitivity demonstrated, during this anonymous exercise was remarkable. Sometimes indicators of a writer’s sophistication were apparent by his/her spelling or handwriting, but each idea was considered on its merits, and responded to with care.

The spring seminar included the use of film as a medium as well. As the conversation turned to schools like PFS, the group decided to watch excerpts of “Voices from the New American Schoolhouse” by Danny Mydlack about the Fairhaven School in Maryland. Conversation then travelled to the challenge of explaining Sudbury-model schools to those who ask, “What grade are you in?” and “What’s your favorite subject?” No easy answers were reached, but the exchange was rich, and its very existence demonstrated to me, again, the power of non-coercive education. These were the closest things to “classes” that I had engaged in since leaving my post at UPenn, where I taught in the Graduate School of Education. Yet even in that Ivy League setting, I rarely saw the kind of profound inquiry in a community of equals that I witnessed in those seminars. I am grateful to Karen and each of the participants for taking the risks required to enable such a learning environment.